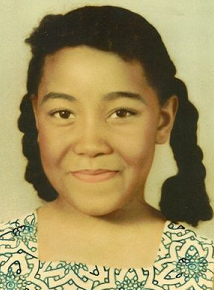

Carole Robertson Day

Carole Robertson Day is held in memory of Carole who was a member of the Jack and Jill teen group in Birmingham, Alabama. She was killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 15, 1963. At the Jack and Jill National Convention in San Francisco, it was decided by resolution that all chapters would honor her in September with an activity that would highlight the goals of human rights, civil rights and racial harmony that Carole did not live to enjoy. She was 14 years of age at her death and she was at the church preparing to march with other youth that day for civil rights. Her mother was the Regional Director for the Southeastern region.

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was an important place for activists during the Civil Rights Movement. It was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions ensued when the southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Congress on Racial Equality became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.

On Sunday, Sept. 15, 1963 at 10:22 a.m. a bomb exploded at the church killing Denise McNair (age 11), Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Carole Robertson (age 14) and Cynthia Wesley (age 14). Twenty three other people were also injured. The four girls had been attending Sunday school classes at the time.

Instead of slowing the growing civil rights movement in the South, the killings fueled protests that helped speed passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which made racial discrimination in public places, such as theaters, restaurants and hotels, illegal. Additionally, employers were required to provide equal employment opportunities.

About Carole ~

Born April 24, 1949, Carole Rosamond Robertson was the third child of Alpha and Alvin Robertson. Her older siblings were Dianne and Alvin. Her father was a band master at an elementary school, and her mother was a librarian.

She was an avid reader and straight-A student who belonged to Jack and Jill of America. Carole was also active in the Girl Scouts, the Parker High School marching band and science club. She attended Wilkerson Elementary School where she sang in the choir.

Carole grew up in Birmingham’s Smithfield community, developed in the early 1900s as a neighborhood for prominent Black professionals. Many homes in the district were designed by the notable Black architect Wallace A. Rayfield. “That home was full of love, friends and the aroma of good cooking, especially her mother’s spaghetti,” remembered Florita Jamison Askew, a childhood friend of Carole’s, in a 2001 article in the Birmingham News. “There was a lot of warmth in the house. The food was good and the people were kind. That was kind of my second home.” Askew and Robertson took lessons in tap, ballet and modern dance, at the Smithfield Recreation Center’s auditorium every Saturday afternoon. “We didn’t have any problems getting our chores done so we could get to dance class on Saturdays,” said Askew. “Nobody ever wanted to miss them.” She said the girls worked hard on their ballet and shuffle steps in preparation for the annual spring recital, where they got to wear makeup and dance with their hair down. Inside Carole’s one-story home with the wrap-around porch, Askew and the Robertson girls practiced dances such as the cha-cha and tried out different hairstyles often on Carole, who didn’t mind being the model. Carole once told Askew, now a retired dentist, about her desire to preserve the past. “I remember a statement she made that she wanted to teach history or do something historical. I thought how ironic it was that she would remain a part of history forever.”

Carole’s Legacy ~

In a 1993 article in Essence magazine, internationally known activist Angela Y. Davis, recalled growing up with Carole. Following are excerpts from that article: “I had known Carole Robertson for almost as long as I could remember. Carole was a few years younger than I; my younger sister Fania’s age. Her sister Dianne was my friend, so Carole was more like a baby sister. I was in France, preparing to study at the Sorbonne, when I learned about the bombing. In tears, I rushed to place a telephone call to my parents, hoping all along that the [news] paper was mistaken. On the day I found out about the bombing, all I could think about were Carole’s bangs and beautiful long braids.” “My mother told me that Carole had just called her a few days earlier to ask for a ride to a meeting of the newly formed organization Friendship and Action. In light of school-desegregation orders, a group of Black and White parents and teachers had established this organization as a way of ‘letting our children get to know each other’ and of developing grass-roots activist challenges to racism in the schools. Carole, my mother said, wanted to get involved and was extremely excited about this meeting.”

“What bothers me most is that their names have been virtually erased: They are inevitably referred to as “the four Black girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing.” I would like to remember not only the terror that claimed her life and that of her Sunday-school friends, but also the positive lives they claimed for themselves as teenage girls. Along with our memories of that horrible day and what it symbolized, I would also like us all to consider what Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins and Denise McNair might have become.”

Remembering Carole ~

At the 25th anniversary celebration of Jack and Jill of America, Inc., during the Eastern Regional Conference in Philadelphia, the following resolution was adopted: “… an award is to be given each year to an outstanding high school graduate in memory of Carole Robertson. This award is to be given in honor of her memory and to inspire young people to reach for the best.” The award is given annually in each region at the teen conferences.

At the 1964 National Convention in Seattle, Jack and Jill of America Inc. paid tribute to Carole Robertson at the Carole Robertson Recognition Night and decreed that in September each chapter is expected to highlight those goals of human rights that Carole did not live to enjoy.